We went diving with the Apple Watch Ultra

In September, Apple launched the Apple Watch Ultra, which is not only waterproof to 100 meters (330 feet) in depth, but can also be used as a dive computer with the help of a companion app developed by Huish Outdoors. The app launched officially today, but we took a pre-release version of it into the deep blue sea to test it out.

I’ve been an enthusiastic scuba diver for more than a decade. I’ve logged hundreds of dives, and I’ve earned a handful of qualifications over the years: I’m an SSI Rescue Diver, an SSI Master Diver and a PADI Divemaster; I’ve also completed a bunch of specialty training over the years. If that means nothing to you, suffice it to say I’m trained in dive-specific first aid, and if you are diving with me, I can (at least in theory) save your life if something goes wrong. I’m also qualified to lead dive tours.

I’m also a big hardware and gadgets nerd, so when Apple first announced that the Apple Watch Ultra could be used as a dive computer, I got very excited and brazenly wrote that I would gladly trust my life to the freshest and chunkiest wrist-worn supercomputer from the Cupertino-based electronics manufacturer. The article got me some, er, interesting feedback from the dive community, but I stand by it. So when Apple gave me early access to the Huish Outdoors Oceanic+ app and an Apple Watch Ultra, I decided to put my money where my regulator goes, book a flight to Hawaii, and see if it could stand the pressure of 100 feet of seawater under my watchful eyes.

Was I nervous? Not really. A dive computer can fail without putting divers’ lives at risk. That said, I should mention that while the Apple Watch Ultra is in its full and final form, the Oceanic+ app was not. I was running a beta version, which did introduce a couple of nerves. The watch app was full-featured and worked sleekly, but the iPhone compendium app was a little rough at the edges, still.

The Oceanic+ watch app itself is where the brunt of the heavy lifting is done, so I’ll spend most of my focus there, but let’s start with a slight detour into some theory…

What’s a dive computer?

If you’re a veteran scuba diver, you probably don’t need this refresher, but for this review to truly make sense, we need to get a little bit nerdy about what a dive computer is and why it’s important to use one.

You may have heard of “the bends,” or decompression sickness. This is a potentially medically serious condition that can occur when you breathe a gas (usually air) at pressure (such as underwater). The problem is that when a gas is at pressure, it goes in through your lungs, and the nitrogen in the gas gets absorbed into your bloodstream. From there, it goes everywhere your blood goes – your muscles, your fat, your brain, your guts, and all your other tissues. This isn’t dangerous in itself, as long as the gas stays “in solution” – in other words, as long as your blood stays liquid, your fat stays fat, and your brain stays sans air bubbles.

If you reduce the pressure too quickly, for example, by surfacing from a dive too quickly, physics flexes its mighty arms (in the form of Boyle’s Law), and that gas can come out of solution, forming little bubbles. Those little bubbles can collect in places you don’t want them and cause very serious issues. A small air bubble in a blood vessel in your brain can cause an embolism. The same air bubble in your heart can cause heart attacks and air anywhere there shouldn’t be air can cause a number of other nasty effects. “Minor” issues are also possible, which can lead to rashes, itches or other unpleasantness. If you want a deep dive into all the nasty stuff that can happen, feel free to Google decompression sickness and dive injuries, and you’ll come across some gnarly shit.

The quirk that complicates all of this is that different tissues take on and release nitrogen at different rates, so you need to keep a close eye on things.

A scuba diver observes that the target 30-minute dive time alarm has been reached. Image credit: Bang Bang Media.

For recreational scuba divers, there is a pretty straightforward way of avoiding decompression sickness:

- When diving, divers tend to the deepest part of their dive first, and then gradually and slowly go shallower and shallower on their dive, ensuring they don’t ascend faster than a certain ascent rate. A dive computer helps here: It will warn you if you are ascending too fast.

- When diving, ensure that they don’t stay down too deep for too long so slow-loading tissues don’t get overloaded with nitrogen. Slow-loading tissues also offload more slowly, and they can cause problems even if you stick to all the other rules of diving. A dive computer will help here, too, by using algorithms to keep a model of how much each of a diver’s tissues are loaded with nitrogen and advise divers to go shallower or to end a dive if they are overloaded. (The algorithm Oceanic+ uses keeps track of 16 different theoretical tissue types, weighted in different ways to keep recreational divers as safe as possible.)

- Finally, divers can give themselves some surface time between dives to properly give their body time to off-gas. In addition to diving, it’s important not to go mountaineering or get on a plane too soon after diving, and don’t dive too deep or too often in rapid succession. How do you keep track of all of that? You guessed it: A dive computer.

In the early days of scuba diving, before dive computers were a thing, you’d use a depth gauge and a watch. Your depth gauge would measure how deep you went, and your watch would be used to keep track of how long you stayed down there. And to calculate how much time you could spend underwater, you’d use dive tables. These early dive tables were calculated by essentially testing on daredevil navy divers in the early 1900s.

As you might expect, they had some issues: Most of the people in the tests were male, 18-25 years of age, and in very good shape. I can just about pass for male, but the rest of those things are not true for me. The other problem is that the dive tables don’t really have a concept of multi-level dives: They assume that you plunge to a certain depth (in the case of a navy diver, plant explosives on an enemy ship), stay there to do a job and then resurface. That’s not really how people dive for fun anymore.

So as soon as dive computers became reasonably accessible, people started using those instead. The first dive computers became available in the 1980s, and they started being reasonably priced – putting them in range of recreational divers in the late 1990s. They could beep at you when you ascended too fast, keep track of your tissue loading, and keep track of multi-depth, multi-dive scenarios that quickly become too complicated to figure out by hand. Some dive training still includes the use of dive tables to support teaching the theory and history, but the vast majority of divers don’t use those after they pass their certification.

The Oceanic+ app uses the Bühlmann decompression algorithm, which is widely used and trusted across the dive industry.

So do you need a dive computer to keep you safe?

As part of your dive training, you are taught how to surface safely from a dive. While a dive computer telling you how fast you are ascending can be a good safety blanket, if your computer should fail and all your other instruments also crap the bed, you can still safely make it back to the boat.

A trick most divers are taught is to “ascend at the rate of your smallest bubbles.” In other words, they breathe out through their regulator, and waft their hand through the bubbles that form. Find the smallest bubble; it will be ascending very slowly through the water. Keep pace with it all the way to the surface, and you will be ascending at a safe, slow rate.

Now, if your dive computer did fail, a safe, conservative diver wouldn’t choose to dive again that day. In theory you could buddy up with a diver who had a more aggressive dive profile than you in previous dives (i.e. they went deeper for longer than you) and you could assume that their dive computer’s data would be safe for you, too. If you stay shallower than them on the next dive, you should, in theory, be fine. However, if you dive on different gases (say, your Nitrox mix was 32% and theirs was 30% oxygen), or if they have done fewer dives than you recently, things get tricky.

In addition, a dive computer is a personal safety device. If you did end up with decompression sickness, the dive medics at the hyperbaric chamber will use the data from your dive computer to figure out what happened and how to treat you. In theory, because no sensible divemaster will recommend you use someone else’s dive computer as a proxy for your safety, most dive operations will ask you not to, and no dive certification body will condone this sort of thing. I would explain all of that to you, and then I’d add — hey, as a certified diver, you’re responsible for your own safety; you do what fits with your acceptable risk profile.

All of this is to say that it isn’t actually dangerous or scary to trust my diving experience to a brand-new Apple Watch and the beta version of an app. I did dive with a second dive computer in the pocket of my Buoyancy Compensator Device (BCD – that’s the life-vest-looking thing you can see in the pictures), so I had something to compare the Apple Watch Ultra with.

If the watch or the Oceanic+ app had failed, I would have had a chance to go on the second dive, relying on my backup computer. I should add that this isn’t uncommon for me: Whenever I’m working as a divemaster and leading other divers, I typically bring two dive computers — one for my wrist and one for in my pocket.

With all of that out of the way… a lot of this is about trusting the gear you are using, which brings me to the next question.

The dive computer I use as a backup is a Suunto Zoop. There are dive computers that are smaller than the Apple Watch Ultra – this is not one of them. The Zoom is now discontinued, but it is the size of an ice-hockey puck, and about as elegant. It does the trick of measuring your dive, however. These days, I keep it in a pocket as a backup. Image Credit: Haje Kamps / TechCrunch.

How do you know if you can trust a dive computer?

As mentioned, if your dive computer fails, you can still safely surface, but it would ruin the rest of your day of diving. Nobody wants to miss out on diving while on an expensive dive trip, so to know whether or not you can trust a dive computer, you need to trust a few different components of it:

- The instrumentation – A dive computer needs to keep a running log of time and depth. Most dive computers run a continuous calculation of your tissue loading, and in addition keep a log with certain intervals, so you can review your log later.

- The algorithm – Different algorithms use different levels of conservatism (i.e. how much safety buffer it has built-in, keeping in mind that everyone’s body is slightly different).

- Reliability – It is exceedingly rare that a dedicated dive computer crashes. It may run out of battery, but as a single-function device that only has to keep track of a single set of algorithms, there’s not much that can go wrong.

Evaluating the Apple Watch Ultra and the Oceanic+ app, then, becomes a question of examining the instrumentation, the algorithm and the reliability.

For instrumentation, Apple claims that the Apple Watch Ultra is EN13319-compliant; this is a European standard covering the “Functional, safety, and testing requirements” for “depth and time measuring devices.” In other words: dive computers. Apple Watch Ultra uses depth sensors that are accurate to 40 meters/130 feet. Typically, a newly certified scuba diver is licensed to 18 meters/60 feet, but most scuba diving training orgs will offer a “deep diving” specialty, which will allow divers to go to the full 40 meters/130 feet depth. Beyond that, you are looking at “technical diving,” which usually requires diving with other gas mixes. Things get complicated fast from here.

The algorithm and the user interface for Oceanic+ is offered by Huish Outdoors, which knows a thing or two about scuba diving. The company owns a number of extremely well-respected scuba diving brands, including Atomic, Bare, Stahlsac, Zeagle, Hollis, and, of course, Oceanic.

So the Oceanic brand itself is trustworthy and has been serving the dive community for 50-plus years. The other diving brands in the Huish Outdoors portfolio are extremely highly regarded and are trusted by recreational, technical and industrial/military divers all over the world. The question mark for me is that the brand doesn’t necessarily have a strong core competency as an app developer.

The truth is that Apple did choose Huish Outdoors as its launch partner to release the Oceanic+ app, giving the developer a significant head start, with the combo receiving hundreds of hours of testing, both in pressurized chambers and in real-life dive conditions. Sources within Apple suggest that other app developers will be given access to the depth sensors later this year, and it’ll be interesting to see what other brands decide to release their own versions of these apps.

The final piece is reliability. I have not experienced crashes with Apple Watch apps before, but it stands to reason that they could happen, as they could with any other app on any other platform. Incidentally, this is where Oceanic+ is, as of yet, an unknown.

Two out of the 40 or so divers that were with us on this Oceanic+ testing extravaganza experienced issues with the Oceanic+/Apple Watch Ultra combo. It’s not entirely clear if this was a user error or whether the app malfunctioned in some way. I didn’t experience any issues, and I’m not clear on whether I ought to be worried. I asked Apple about this, and they said they are unable to comment on specific incidents with beta software.

Personally, if the Oceanic+ app had failed or crashed on my dives, I’d have been a little grumpy, but as described above it doesn’t present an actual risk to divers. If you notice the app is malfunctioning, you can surface slowly and safely. Huish Outdoors did release an update of the beta app as I was writing this review, and will have its final release ready in the public App Store as you are reading this.

Your correspondent greeting the photographer underwater. You can see the Apple Watch Ultra on my left wrist, facing toward me, and that I am in dire need of a haircut and a shave. Image credit: Bang Bang Media.

As above, so below

Oceanic+ is a sleek, powerful Apple Watch app that essentially replicates (almost) everything a dive computer can do, and adds a few new toys to the mix. The app is in active development, and the team developing the app told me they have an extensive roadmap for fun new features it has in the pipeline. First things first, though: Getting the app into people’s hands.

The app has a number of free features which are useful for snorklers and free divers. If you want to use it as a dive computer, however, you have to pay its (remarkably well-designed) subscription fee to unlock the full functionality.

https://techcrunch.com/2022/11/28/oceanic-plus-pricing-model/

A diver inspecting their dive profile on the Apple Watch Ultra, observing it has been 1 hour and 11 minutes since their dive (known as the “surface time.”) Image credit: Bang Bang Media.

At the surface, the watch can be used for dive planning and a log book, and to configure the settings for your next dive. If you have a recent dive on the books, it can also show you your surface interval time.

None of this is rocket science; dive computers have been able to do most of these things as long as they have been around. The Apple Watch Ultra’s huge touch-screen makes the user experience significantly nicer than on traditional dive watches, which can be pretty indescipherable from time to time. Think user interfaces that seem like relics from the 1980s Casio watch era, and you get a pretty good idea.

Dive Planner, Dive Mode and the logbook are all easily accessible when you’re at the surface. Image Credit: Apple.

Dive planning helps you use your current tissue loading to figure out how deep and how long you can dive for after a surface interval.

The log book helps you see the depth profile of your recent dives, along with dive time, max ascent rate, water temperature, maximum depth and the gas mix (air at 21% oxygen or Nitrox up to 40% oxygen), sampled every 15 seconds as you are underwater. These are features you can get on any dive computer, but Oceanic+ also shows any warnings about your recent dives, and uses the GPS chip in the watch to show a map of where you dived. Small iterations, but they make a huge difference over traditional dive computers.

Dive settings, Scuba settings, and the dive alarm configuration screen. Image Credit: Apple.

Finally, you can configure settings for your dive, including the units you want to set your app to (Celcius or Farenheit, feet or meters, pounds or kilos) and dive mode (snorkeling or scuba), and scuba settings (partial oxygen pressure and gradient factor settings, which are safety settings usually left to advanced divers, or divers who have body compositions or medical conditions that warrant being extra careful). You can also configure your gas (air or Nitrox) and Nitrox oxygen level settings.

You can also set up dive alarms: a depth alarm to warn you when you’ve reached a certain depth and a dive duration alarm. Both are helpful to ensure you stay within your dive plan. It’s also possible to configure whether the watch automatically starts tracking dives when it senses you’ve hopped into the water or whether you need to start the dives manually.

It’s possible to review the dive or adjust settings at the surface. As soon as you submerge, water lock automatically engages, and the touch screen is disabled. Image Credit: Bang Bang Media.

In the iPhone app, you can add additional notes about your dive: visibility, currents, notes about who you dived with, wildlife you saw, equipment you used, or other notes you want to take. You can also add your dive certification cards and numbers and other helpful notes.

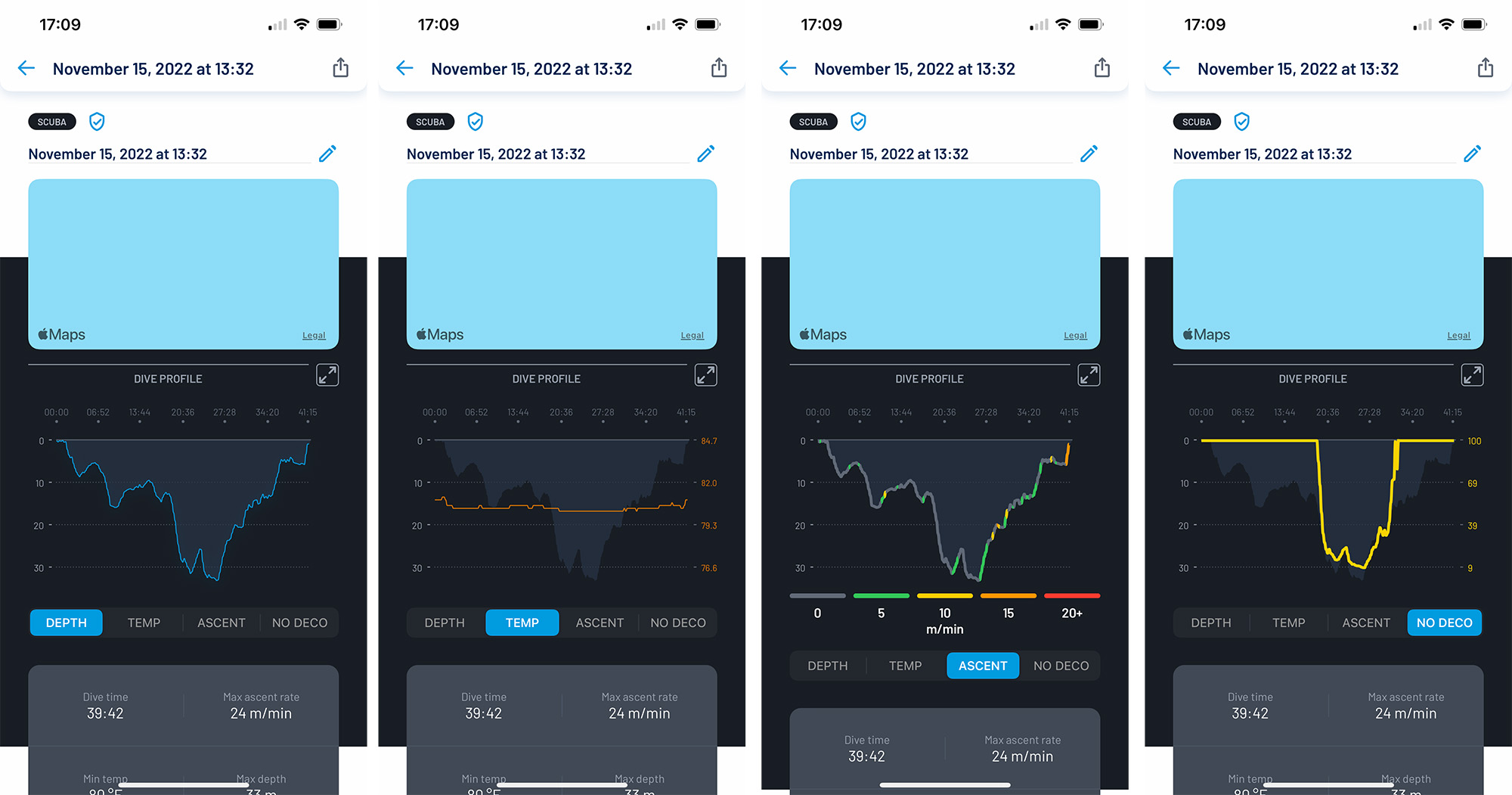

For example, in the screen shot below, the post-dive information shows the depth profile of my dive, along with my max ascent rate (24 meters per minute). The recommended ascent rate is a maximum of 18 m/s, so the watch gave me a warning that I was being silly.

Image Credit: Screenshot from Apple Watch

Also in the app, you can plan your next dive by selecting the dive site on a map, and see recent water temperatures and other data about the dive.

Over time, the company told me it is planning to make this data crowdsourced, so divers who have been at the site recently can give you higher-resolution ideas of the temperature, visibility, currents and perhaps even wildlife spotted at various sites. Helpful if you are looking for whales or other large sea creatures!

The iPhone app still needs a little bit of work, but even with some minor graphic inconsistencies and quirks (mostly text alignment, minor typos, etc.), it gives a very good post-dive experience:

From left to right: depth chart, temperature chart, ascent rates, and remaining no-deco time. Image credit: Oceanic+ screen shots

As you can see from the screenshots, the Apple Maps preview was possibly zoomed in a little bit too far; yes, I was diving in the ocean, but without any visual cues for where I was, the map isn’t that useful.

The depth chart, temperature, ascent rates, and no-decompression (no-deco) graphs are fantastic tools for divers, however. Most dive computers let you connect to your computer with USB or Bluetooth; it was refreshing to see how seamless the Oceanic+ experience was. By the time I opened my iPhone, all my data was already synced and ready to dig into.

Taking it into the water

Yours truly wearing the Apple Watch Ultra. It’s very comfortable to wear with all its different wristbands, but it is a comically large watch. Let’s ignore that I’m using an Android phone in this photo, shall we. Image Credit: Bang Bang Studios

For normal use, the Apple Watch Ultra takes some getting used to. It is a very large watch, and on my puny little computer-nerd wrists, it looks comically huge. That issue goes away once I’m in the water, though; large as it is for a watch, it is about on par with an average dive computer.

In the ocean, the Apple Watch Ultra is truly in its element. The display is large, fantastically bright and very easy to read under water. Apple says it is the largest display ever on an Apple Watch, and twice as bright as the display on the Series 8.

I would be amiss if I didn’t mention the water sports band Apple has created for the Apple Watch Ultra. The ‘Ocean Band,’ as the company calls it, was designed specifically for ocean and water activities, molded from a high-performance elastomer.

The tubular geometry allows it to stretch for a perfect fit, and the titanium buckle and adjustable loop means that once it’s on, it ain’t coming off easily. The band was designed for extreme water sports, including kite surfing and other high-impact sports. Great for clumsy scuba divers like myself. I tried to rip the watch off underwater, and failed. It’s remarkably sturdy.

The company even sells a band extension if you need to wear the watch over a drysuit or a particularly chonky wetsuit.

The underwater readability of the Apple Watch Ultra is extraordinary – and pretty hard to photograph, so you’ll have to take my word for it, I’m afraid. Image Credit: Bang Bang Media.

Once you activate dive mode, the watch enters water-lock mode, which means that the touch screen becomes unusable, and you have to rely on the Digital Crown (which is 30 percent bigger than Series 8 with coarser grooves) and two buttons to engage with its functions.

In addition to the crown and the side button, both of which are slightly raised so they can be easily used even when you are wearing gloves, the Apple Watch Ultra has an orange Action button. When diving, this can be used to dismiss warnings and alarms, and to select a compass heading on the underwater compass.

The crown is protected by a titanium guard to help prevent accidental rotations, and the sapphire glass on the watch is protected by a titanium bezel all the way around. All great features to have on a dive computer.

The watch uses water-based sensors only during a dive: depth gauge, water temperature, and the compass, in addition to the time. You don’t get the vital readings (heart rate, etc.) that you would get on a run, which I think makes a lot of sense. Apple suggests that measuring vitals is hard to do consistently underwater, and in any case I ended up wearing the Apple Watch Ultra over a wetsuit anyway, so it couldn’t have made a reading if it had wanted to.

In use in the deep blue sea

Once a dive is started and the water lock mode is on, you can use the Digital Crown to scroll through a number of information screens. On all screens, you can see your current depth and no-deco time. Always on screen is also a variometer, which moves up and down as you ascend or descend. It can be remarkably hard to determine whether you are moving up and down in open water, so that’s a very helpful tool to keep you level in the water, for example when doing a safety stop.

Primary screen, Secondary screen, Compass screen, and the Air screen. Image Credit: Apple.

You can rotate the Digital Crown to access additional screens or press the Action button to set a compass heading. On the various screens, divers get access to a bunch of extra information.

Primary screen:

- Dive Time – helpful to know how long you’ve been under, and when the boat expects you back

- Minutes to Surface – how long would it take to safely ascend to the surface, including a safety stop

- Water Temperature – never really all that helpful, as there is not much you can do about it once you’re in the water and realized you didn’t wear a warm enough wet suit

Secondary screen:

- Max depth for this dive – helpful to ensure you are sticking to the outlined dive plan for this dive

- Current ascent rate – good to keep an eye on when you are surfacing from your dive to ensure you are ascending at a reasonable rate

- Percentage battery left in the Apple Watch Ultra – the battery life on this thing is extraordinary, but it’s good to be able to check

Compass screen:

This is a super helpful screen; underwater compasses are crucial, and often one of the only ways to know which way you are facing underwater. Traditional compasses are a royal pain in the wetsuit to use, and the Oceanic+ app has one of the best implementations I’ve ever seen.

- Current compass bearing

- Target compass heading (set using the Action button)

Air screen:

This screen confused me a little; I doubt it’d come in all that helpful most of the time, but it’s neat to be able to verify that your watch is using the settings you thought it was.

- Conservatism

- Gas settings – air vs Nitrox, and oxygen percentage if you’re diving on Nitrox

- Max oxygen partial pressure setting. This is good to know, as oxygen can become toxic to the central nervous system at high partial pressures. Here’s a “fun” fact for you: Oxygen can be toxic to humans if you breathe pure 100% oxygen at as little as 6 meters/20 feet deep.

In addition, the watch will use a powerful haptic signal, easily felt through a wetsuit, to draw your attention to it when it needs to tell you something.

It can give safety warnings such as decompression limits, excessive ascent rates and safety stops. It can also warn you if you’re at your maximum operating depth (which varies based on what gas you are breathing), and buzz you with any depth or time alarms you have set.

The alarms are very well color coded: Red for things that need immediate action, yellow for warnings, and blue if the water temperature drops below your configured threshold. And the large, bright screen and prominent haptics means you’re not going to miss anything.

Below are some examples of the warning screens: too-rapid ascent warning; safety stop reminder; target depth alarm; and temperature alarm. The green lines across the middle of the screen is the tissue loading. If it goes all the way down, you are out of no-deco time, and it’s time to surface to avoid unnecessary risk of decompression sickness.

Image Credit: Apple.

Once in the water, there is remarkably little to say about the Apple Watch Ultra as a dive computer: It’s easy to use; the crown and buttons are phenomenal as far as user interfaces go, the screens are well-designed; and the important information is clear and very easy to read.

I brought my trusty old Suunto that has been with me on many a dive to serve as my secondary dive computer for these test dives. The readouts from the two dive computers were almost identical all the way through. The small differences can be attributed to having the Suunto in my pocket while the Apple Watch was on my wrist.

The Suunto also uses a slightly different algorithm. Having said that, trying to compare the dive profiles on the two devices reminded me why the Oceanic+ was such a great leap forward. Even figuring out how to step through a logged dive on the Suunto is an unmitigated, miserable disaster. We’ve come a long way in dive tech.

Easy to read underwater. Image Credit: Apple

What is missing?

Apple Watch Ultra plus Oceanic+ is a hell of a combo. It’s heads and shoulders above the competition in terms of screen and user interface, and the automatic syncing and logging to my phone is a fantastic perk. Which isn’t to say that the Apple Watch does quite everything yet.

Most high-end dive computers are “air integrated,” meaning that a transmitter can be added to your first-stage regulator, which transmits how much air you have left in your tank to your dive computer. Rumor has it that Oceanic+ and Apple Watch Ultra might have something in the works to add air integration at some point in the future, although both companies remained tight-lipped on if and when when this might be available.

As you climb closer to the $1,000 mark, dive computers are also able to do more exotic gas mixes, mostly used for technical diving. They are also better at doing decompression diving, which is dives where you exceed your no-deco time, and need to stay underwater for longer to off-gas.

I suspect the Oceanic+ app has deco algorithms in place to save your bacon in case divers accidentally overstay your no-deco time, but I wasn’t able to verify this before this article was published. Again, not something you would expect recreational divers to run into on the regular. For context, in my hundreds of dives, I have only ever once had to do a decompression dive; it involved staying at 10 meters for 6-7 minutes extra.

One advantage the Apple Watch Ultra has over traditional dive computers, however, is that most dive computers spend 11 months of the year in a drawer, whereas Apple’s device can be used for, well, the hundreds of things that people use Apple Watches for, including making calls, fall detection, health tracking, notifications and much more. On a cost-per-day-used basis, the Apple Watch Ultra is an absolute bargain compared to every dive computer on the market today.

I can’t help but wonder if we have entered a similar space for dive computers that we saw for sat-nav devices some 15 years ago. If you’ll recall, in the time before iPhones, there was a period where everyone had dedicated sat-nav devices from manufacturers like TomTom and Garmin. When the iPhone came along, they delayed their own demise in this space by releasing mapping apps for the new phone platform with significant price tags, before they were all destroyed by the likes of Google Maps, Apple Maps, Waze and other free mapping apps with live traffic data.

It wouldn’t surprise me if at some point in the non-too-distant future, as prices of Apple Watch Ultra and similar devices come down, dive computers will seem as anachronistic as using a suction-cup to put a Garmin device on your windshield does today.

Sup. Image Credit: Bang Bang Media.

Should you take the plunge?

Time will tell if an $800 watch is accessible enough to put a major dent in dive computer sales. After all, $500 buys you a great entry-level dive computer. It is admittedly far larger than the Apple Watch Ultra, and not nearly as nice or as easy to use as the Apple/Oceanic+ combo. A higher-end dive computer, however, like Suunto’s D5 or Oceanic’s own ProPlus 4 computer, cost about the same as the Apple Watch Ultra.

Would I recommend that you trust your dive holiday to an Apple Watch and an Oceanic+ app? Yes, with a caveat. I would need a few more dives with a backup dive computer in my BCD pocket before I would rely on the Oceanic+ app by itself.

I’d trust it as long as Huish Outdoors ensures that the stability and reliability of the app remain its No. 1 priority over all the fun bells and whistles it could be tempted to add over the next months and years. And if the app continues to stay stable, I can’t imagine it will take very long before the skeptic in me fully embraces it.

🤙 Thanks for reading, see you on the reef! Video credit: Bang Bang Media