Lensa AI, the app making ‘magic avatars,’ raises red flags for artists

If your Instagram is awash in algorithmically generated portraits of your friends, you aren’t alone. After adding a new avatar generation tool based on Stable Diffusion, the photo editing app Lensa AI went viral over the last few days, with users sharing their uncanny AI-crafted avatars (and the horrible misfires) in stories and posts.

Lensa’s fun, eminently shareable avatars mark the first time that many people have interacted with a generative AI tool. In Lensa’s case, it’s also the first time they’ve paid for computer-generated art.

Stable Diffusion itself is free and a lot of people are playing around with it for research purposes or just for fun. But Lensa and other services like it — Avatar AI and Profilepicture.AI, to name a few — are making money by selling the computing cycles required to run the prompts and spit out a set of images. That certainly changes the equation a little.

Lensa is built on Stable Diffusion’s free, open source image generator but acts as a middleman. Send Lensa 10-20 selfies and $7.99 ($3.99 if you sign up for a free trial) and the app does the heavy lifting for you behind the scenes, handing back a set of stylized portraits in an array of styles like sci-fi, fantasy and anime. Anyone with sufficient processing power can install Stable Diffusion on a machine, download some models and get similar results, but Lensa’s avatars are impressive and Instagram-ready enough that droves of people are more than happy to pay for the convenience.

While the tech world has celebrated the advancements of AI image and text generators this year — and artists have watched the proceedings warily — your average Instagram user probably hasn’t struck up a philosophical conversation with ChatGPT or fed DALL-E absurdist prompts. That also means that most people haven’t grappled with the ethical implications of free, readily available AI tools like Stable Diffusion and how they’re poised to change entire industries — if we let them.

From my experience over the weekend on Instagram, for every 10 Lensa avatars there’s one Cassandra in the comments scolding everyone for paying for an app that steals from artists. Those concerns aren’t really overblown. Stable Diffusion, the AI image generator that powers Lensa, was originally trained on 2.3 billion captioned images — a massive cross-section of the visual internet. Swept up in all of that is all kinds of stuff, including watermarked images, copyrighted works and a huge swath of pictures from Pinterest, apparently. Those images also include many thousands of photos pulled from Smugmug and Flickr, illustrations from DeviantArt and ArtStation and stock images from sites like Getty and Shutterstock.

Individual artists didn’t opt in to appearing in the training dataset, nor can they opt out. According to LAION, the nonprofit that created the huge datasets to begin with, the troves of data are “simply indexes to the internet,” lists of URLs to images across the web paired with the alt text that describes them. If you’re an EU citizen and the database contains a photo of you with your name attached, you can file a takedown request per the GDPR, Europe’s groundbreaking privacy law, but that’s about it. The horse has already left the barn.

We’re in the earliest stages of grappling with what this means for artists, whether it’s independent illustrators and photographers or massive copyright-conscious corporations that get swept up in the AI modeling process. Some models using Stable Diffusion push the issue even further. Prior to a recent update, Stable Diffusion Version 2, anyone could craft a template designed to mimic a specific artist’s distinct visual style and mint new images ad infinitum at a pace that no human could compete with.

Andy Baio, who co-founded a festival for independent artists, has a thoughtful interview up on his blog delving into these concerns. He spoke with an illustrator who discovered an AI model specifically designed to replicate her work. “My initial reaction was that it felt invasive that my name was on this tool,” she said. “… If I had been asked if they could do this, I wouldn’t have said yes.”

By September, Dungeons & Dragons artist Greg Rutkowski was so popular as a Stable Diffusion prompt used to generate images in his detailed fantasy style that he worried his actual art would be lost in the sea of algorithmic copies. “What about in a year? I probably won’t be able to find my work out there because [the internet] will be flooded with AI art,” Rutkowski told MIT’s Technology Review.

Those worries, echoed by many illustrators and other digital creatives, are reverberating on social media as many people encounter these thorny issues — and the existential threat they seem to pose — for the first time.

“I know a lot of people have been posting their Lensa/other AI portraits lately. I would like to encourage you not to do so or, better yet, not to use the service,” voice actor Jenny Yokobori wrote in a popular tweet thread about Lensa. In another, Riot Games artist Jon Lam shared his own discomfort with AI-generated art. “When AI artists steal/co-opt art from us I don’t just see art, I see people, mentors and friends. I don’t expect you to understand.”

Personally, I was sick and stuck at home over the weekend, where I spent more time than usual idly scrolling on social media. My Instagram stories were a blur of flattering digital illustrations that cost cents a piece. Lensa has clearly tapped into something special there, appealing to both the vain impulse to effortlessly collect 50 stylish self-portraits and the interactive experience of polling your friends on which are your spitting image (most, from my experience) and which are hilarious mutations that only a computer doing its best human impersonation could spin up.

Some friends, mostly artists and illustrators, pushed back, encouraging everyone to find an artist to pay instead. Some creative people in my circles paid too and it’s hard to fault them. For better or worse, it’s genuinely amazing what the current cohort of AI image generators can do, particularly if you just tuned in.

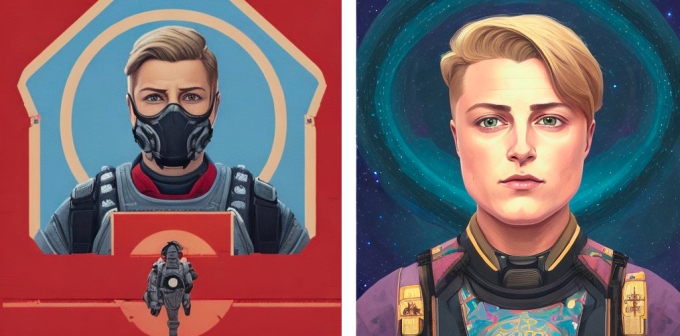

Image Credits: Lensa/TechCrunch

Soon, we’ll all be paying attention. In the name of story research and vanity, I downloaded Lensa and gave the app a try. I’d only paid once for an artist to make me a profile picture in the past and that was just one image, all the way back in 2016. Now for less than 10 bucks I had a set of 50 epic avatars generated from my most me photos, but these were extra me. Me in various futuristic jumpsuits stepping out of the pages of a graphic novel, me in purple robes looking like an intergalactic saint, me, me, me.

I see the appeal. A handful of friends remarked on how the pictures made them feel, hinting at the gender euphoria of being seen the way they see themselves. I wouldn’t fault anyone for exploring this stuff; it’s all very interesting and at least that complicated. I like my avatars, but part of me wishes I didn’t. I don’t plan to use them.

I thought about my own art, the photography I sell when I remember to stock my online store — mostly mountain landscapes and photos of the night sky. I thought back to a handful of the prints I’ve sold and the effort I had to put in to get the shots. One of my favorite photos involved special permission from the National Park Service and a five-hour backpack trek up to a remote fire lookout in Washington. Many entailed lonely hours of tending my tripod alone in the freezing cold, tracking the Milky Way as it rotated above a dark horizon like the hand of a clock.

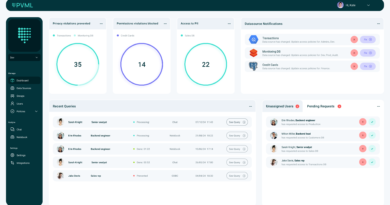

AI Milky Way images from a search of Stable Diffusion images on Lexica.art. Image Credits: Lexica/TechCrunch

The AI models already have enough training fodder to faithfully recreate photos of one tucked-away mountain spot nearby that only local nightsky photographers seem to know about. Three years ago, when I shot photos there, I had to snag a competitive campsite and drive for miles up a potholed forest service road only to wait in the dark for hours. I cooked an expired packet of ramen noodles with a small camp stove to stay warm, tucked the feathers back into my jacket and jumped at everything that made a noise in the dark.

I don’t make a living off of my art. But it still feels like a loss to think that those experiences and the human process they represent — learning how to predict a cluster of ancient stars in the blackness, slipping on wet stones and chipping my hotshoe, keeping extra batteries warm in a down pocket — could be worth less in the future.