Franco Harris not only changed the Steelers, he changed Pittsburgh

Franco Harris came to Pittsburgh and the Steelers in the spring of 1972. Both the city and franchise would never be the same again.

Up until Franco Harris arrived, the Pittsburgh Steelers were losers.

Harris, who died at the age of 72 on Tuesday evening, not only changed the fortunes of a bedrock NFL franchise. He also changed the national perception of a city on the brink of destruction.

Pittsburgh, long one of America’s bastions for industry and in particular, steel, was in trouble. The mills were closing, one by one. The Steelers were no comfort, having won exactly zero postseason games since their inception in 1933, until Harris arrived as a rookie from nearby Penn State in 1972.

Until Harris’ rookie season, the best Pittsburgh had ever done was finish 9-5 in 1962 before losing the defunct Playoff Bowl to the Detroit Lions.

For the three years preceding Harris’ arrival, the Steelers were slowly building. They hired head coach Chuck Noll and selected defensive tackle Joe Greene in 1969. The following year, they selected quarterback Terry Bradshaw in the first round and corner Mel Blount in the third. In ’71, Pittsburgh found a plethora of starters in the draft, including linebacker Jack Ham, defensive end Dwight White, defensive tackle Ernie Holmes and guard Gerry Mullins.

But none of it produced a winning season. Then Harris showed up. So did the wins.

For the first time in franchise history, the Steelers hosted a playoff game after going 11-3, winning the AFC Central. Pittsburgh’s draw was the Oakland Raiders, a perennial postseason power. The Raiders had played in four of the previous five AFL/AFC title games, reaching Super Bowl II.

On Dec. 23, 1972, a frigid day in Pittsburgh, the Steelers and Raiders battled fiercely inside Three Rivers Stadium. The teams traded punts most of the afternoon, until Pittsburgh went ahead in the third quarter on a Roy Gerela 18-yard field goal.

After a fourth-quarter Gerela field goal made it 6-0, Oakland responded behind future Hall of Fame quarterback Ken Stabler. With 73 seconds remaining, Stabler ran 30 yards down the left sideline for the Raiders’ first score. After the extra point, Oakland led 7-6. Hope was lost.

Then, a miracle.

With 22 seconds left, the Steelers faced 4th and 10 from their own 40-yard line. Bradshaw dropped back and evaded the rush, stepped to his right and unloaded down the middle for running back John Fuqua. The ball was broken up by Raiders safety Jack Tatum, the pigskin sent hurdling toward the midfield logo.

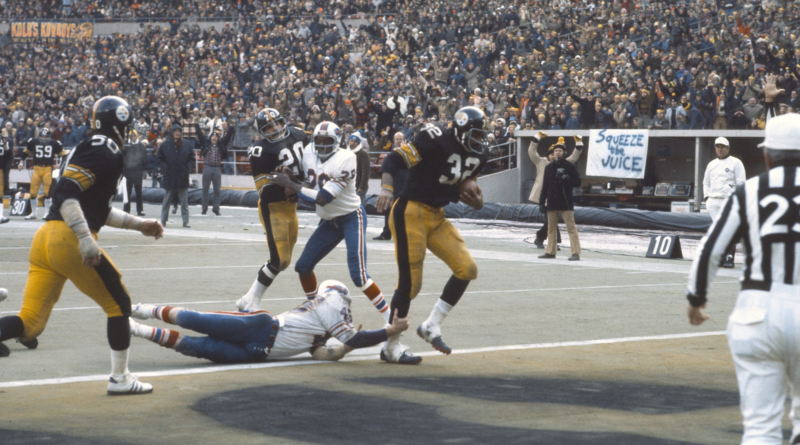

Harris, who was charged with blocking before leaking out into a pass pattern, was jogging upfield with the ball in flight. Suddenly, the football, Harris, Pittsburgh and perhaps divine intervention all met. Harris caught the ball just beyond Oakland’s 40-yard line, broke into the clear and ran down the left sideline to glory.

Pittsburgh 13, Oakland 7. The Immaculate Reception.

Although five seconds remained, madness ensued. Pittsburgh’s entire bench emptied into the end zone. The fans poured over the field’s exterior boundary and joined them. The Raiders screamed illegality, claiming the ball hit Fuqua and not Tatum (at the time, an offensive player couldn’t catch a deflection off his teammate). Bradshaw, who saw nothing after being decked on the throw, thought he made a miraculous play, not yet realizing what had taken place.

For the Steelers, it was the biggest win in franchise history to that point. For the city of Pittsburgh, it was a touchstone moment, a point to revisit in the ensuing years of a burgeoning dynasty.

The Steelers would go on to lose the following week against the unbeaten Miami Dolphins, but two years later, the dreams of both team and city were realized.

Pittsburgh won four Super Bowls in six years from 1974-79, with Harris becoming the NFL’s all-time postseason rushing leader along the way, a mark which stood until Emmitt Smith of the Dallas Cowboys broke it in the 1990s.

All told, Harris played 13 seasons, including 12 with the Steelers. He was the Super Bowl IX MVP, named to the 1970s All-Decade Team, a Pro Bowler each of the first nine campaigns, and earned First-Team All-Pro honors in 1977. Harris was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1990, having amassed 14,407 total yards and 100 touchdowns.

Perhaps most indicative of Harris’ legacy, he was named NFL Man of the Year in 1976.

For many, being remembered at all is a wonderful tribute to the way a man lived. For Harris, he’s remembered by millions for a singular play, subsequently followed by a brilliant career. Yet for those who knew him, Harris’ football prowess is what the man did, not who the man was. By all accounts — evidenced by the tributes flowing in — Harris was a man of character who enriched the lives of those who knew him. That’s the legacy.

As for Pittsburgh, Harris left it far better than he found it. He and his teammates provided myriad memories for those who saw them, and through the storytelling of one generation to another, helped give memories in a different way.

Before Harris, the Steel City was a town known nationally for looming hard times and a few baseball pennants.

In football, Pittsburgh was nothing but a perennial loser.

With Harris, it became was known as the City of Champions.

And it started on Dec. 23, 1972, when Harris made the play of a lifetime.

One which like Harris’ memory, will live forever.