American schools would rather not tell parents just how badly behind their children are after the pandemic

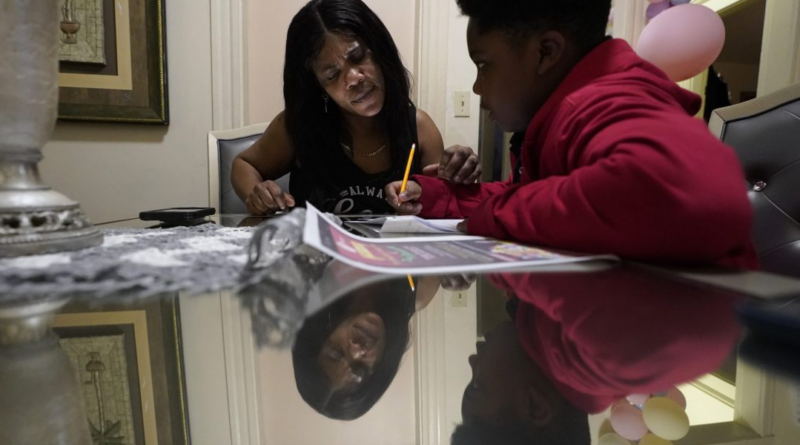

Evena Joseph was unaware how much her 10-year-old son was struggling in school. She found out only with help from somebody who knows the Boston school system better than she does.

Her son, J. Ryan Mathurin, wasn’t always comfortable pronouncing words in English. But Joseph, a Haitian immigrant raising him by herself, did not know how far behind he was in reading — in the 30th percentile — until a hospital where her son was receiving treatment connected her with a bilingual advocate.

“I’m sad and disappointed,” Joseph said through an interpreter. “It’s only because I was assigned an educational advocate that I know this about my son.”

It’s widely known from test scores that the pandemic set back students across the country. But many parents don’t realize that includes their own child.

Schools have long faced criticism for failing to inform certain parents about their kids’ academic progress. But after the COVID-19 school closures, the stakes for children have in many ways never been greater. Opportunities to catch up are plentiful in some places, thanks to federal COVID aid, but won’t last forever. It will take better communication with parents to help students get the support they need, experts say.

“Parents can’t solve a problem that they don’t know they have,” said Cindi Williams, co-founder of Learning Heroes, a nonprofit dedicated to improving communication between public schools and parents about student academic progress.

A 2022 survey of 1,400 public school parents around the country by Learning Heroes showed 92% believed their children were performing at grade level. But in a federal survey, school officials said half of all U.S. students started this school year behind grade level in at least one subject.

At home, J. Ryan races through multiplication problems at his dining room table. His mother watches as he lingers for several minutes on a paragraph about weather systems and struggles to answer questions about the reading.

“Sometimes I can’t understand the writing or the main idea of the text,” J. Ryan said after putting away his homework.

The struggles that ultimately brought J. Ryan to the hospital for mental health treatment began in third grade, when he returned to in-person school after nearly a year of studying online. His teacher called frequently, sometimes every day. J. Ryan was getting frustrated, disrupting lessons and leaving the classroom.

J. Ryan displayed these behaviors during English language arts and other classes including Mandarin and gym, according to his special education plan shared with The Associated Press. He happily participated in math class, where he felt more confidence.

Joseph changed her work schedule at a casino to the night shift so she could talk with teachers during the day. The calls continued in fourth grade. But Joseph said teachers never mentioned his problems reading.

Last spring, she sought treatment for what was becoming obvious: Her son was depressed. She was teamed up at the hospital with the parent advocate who speaks English and Haitian Creole.

The advocate, Fabienne Eliacin, pushed to get J. Ryan’s scores from the tests given each fall to monitor student learning. She explained to Joseph what it meant to be scored in the 30th percentile. It’s not good, Eliacin told her. He can do better.

To Joseph, it suddenly made sense why J. Ryan was acting out in English class. But why, she wondered, were his teachers only focused on her son’s behavior if his trouble reading was causing his distress? “They don’t really care how much they learn, as long as they stay quiet,” Joseph concluded.

Boston Public School officials wouldn’t comment on J. Ryan’s case. “We are committed to providing families with comprehensive and up-to-date information regarding their student’s academic performance,” district spokesperson Marcus O’Mard said.

Before this year, it was up to Boston schools to share midyear evaluations with parents, but it’s not clear how many were doing it. In the fall, Boston rolled out a communications campaign to help teachers explain testing results to parents as much as three times a year.

J. Ryan’s former teachers did not respond to emails seeking comment.

There are many reasons teachers might not talk to parents about a student’s academic progress, especially when the news is bad, research shows.

“Historically, teachers did not get a lot of training to talk to parents,” said Tyler Smith, a school psychology professor at the University of Missouri. School leadership and support for teachers also make a difference, he said.

That’s consistent with findings from national teacher surveys conducted by Learning Heroes. At times, Williams said, teachers also “make assumptions” that low-income parents don’t care or shouldn’t be burdened.

Without these conversations, parents have had to rely on report cards. But report cards are notoriously subjective, reflecting how much effort students show in class and whether they turn in homework.

The progress report for Tamela Ensrud’s second-grade son in Nashville shows mostly As and a B in English, but she noticed her son was having trouble with reading. She asked to discuss her son’s reading test scores at a fall parent-teacher conference, but was only shown samples of her son’s work and told, “Your son is doing well.”

Her son’s afterschool program, which is run by a nonprofit, tested his literacy and math skills this fall and found he was reading below grade level. He qualified for their reading intervention program.

“I don’t think the full story is being told,” Ensrud said.

Metro Nashville Public Schools said it posts student test scores online for parents to see. “To our knowledge she has not shared any of those concerns with the school administration and if she had, they would be able to share information about these resources,” spokesperson Sean Braisted said.

Ensrud has looked at the scores online and found them impossible to interpret.

Many districts have poured their federal pandemic recovery money into summer school offerings, tutoring programs and other interventions to help students regain ground lost during the pandemic. But the uptake hasn’t been what educators hoped. If more parents knew their children were behind academically, they might seek help.

Once Joseph and her advocate learned J. Ryan was so far behind in reading, they asked his school for small-group tutoring, an intervention believed by experts to be one of the most effective strategies for struggling students.

But they were told the school didn’t offer it. They moved him in November to another school that said it could give this help. J. Ryan says he likes the new school, since they’re learning more advanced long-division. “I like challenging math,” he said. But he isn’t understanding the texts he reads much better.

Joseph isn’t getting phone calls from the teacher complaining about his behavior, which she attributes to her son getting adequate treatment for his depression. But she hasn’t received a report card this year or the test scores the district says it’s now sending to families.

“I’m still concerned about his reading,” she said.

___

The Associated Press education team receives support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The AP is solely responsible for all content.