‘We repeated ignition’: Lab behind nuclear fusion breakthrough duplicates success after months of near-misses

The US government lab that last year reached a long-sought milestone in nuclear fusion — achieving a controlled reaction that yielded more energy than it took to produce — has repeated the achievement, after months of near-misses.

Being able to reproduce the Dec. 5 breakthrough may bring the world one step closer to using fusion, which powers the stars, as an abundant source of clean energy. But that future likely remains years off, if it happens at all.

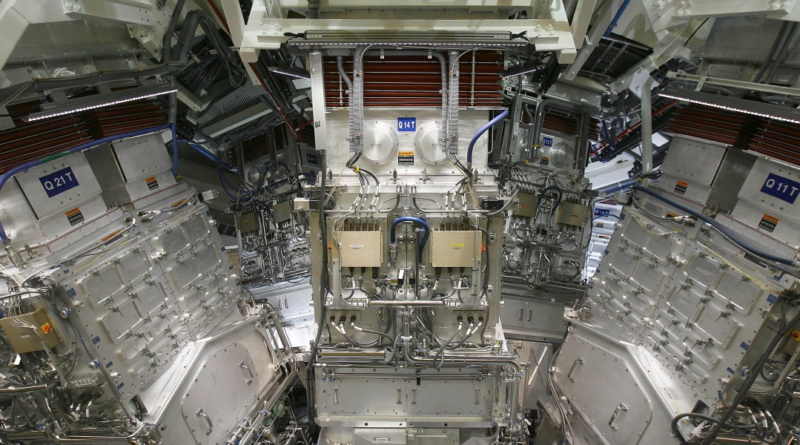

The Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory near San Francisco conducted a series of tests this spring and summer that didn’t quite achieve “ignition,” the point at which energy output from the experiment exceeds the amount pouring in. Each test involves firing the world’s most powerful laser at a tiny diamond capsule filed with hydrogen, compressing the fuel and triggering the reaction. One experiment in June achieved breakeven, with the same amount of energy coming out as went in.

They finally reached ignition again last week, according to a statement Sunday from the lab. The news was first reported by the Financial Times.

“In an experiment conducted on July 30, we repeated ignition,” the statement read. “Analysis of those results is underway. As is our standard practice, we plan on reporting those results at upcoming scientific conferences and in peer-reviewed publications.”

Unlike fission, the process used in current nuclear power plants, fusion involves smashing atoms together instead of splitting them apart. It theoretically can supply carbon-free energy without long-lasting radioactive waste. But generations of scientists have struggled to master it in a controlled reaction, even though it has been the power source of nuclear weapons for decades.

In addition to the process used by the Livermore lab, known as inertial confinement, researchers are still trying to achieve ignition using high-powered magnets to contain a fusion reaction within a donut-shaped ring of plasma. And turning either approach into a steadily running power plant presents its own challenges.