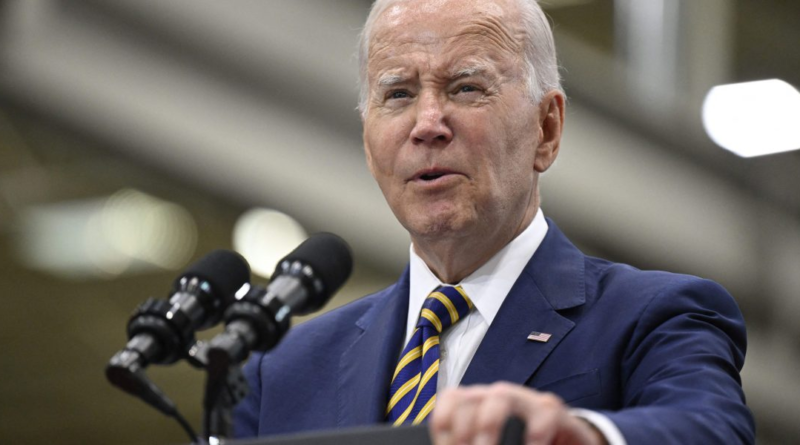

Joe Biden is staking his re-election on an economic policy called 'Bidenomics' that's driving Republicans crazy

A preoccupation within President Joe Biden’s administration is why the president can’t get any love for a relatively strong economy. In hopes of changing things, Biden opted to embrace “Bidenomics” as a shorthand for his economic efforts. The phrase had been popping up for months, usually with negative connotations. Now Biden is staking his claim for a second term on it.

How does Biden define Bidenomics?

He applies it to elements of his domestic agenda that he says are designed to help regular people directly instead of “trickling down” from the well-off. The chief elements are three laws he signed in his first two years: the bipartisan infrastructure law that’s spurring road and bridge building; the CHIPS and Science Act, which boosts manufacturing of semicondicutors inside the US, and the Inflation Reduction Act, which contains hundreds of billions of dollars to fund clean-energy projects and address climate change. Embracing “Bidenomics” publicly on June 28, the president said the phrase also should encompass his efforts to boost labor unions and technical education programs and to promote competition through antitrust laws. He also mentioned his pledges, unfulfilled as of yet, to offer universal preschool for 3- and 4-year-olds and make two years of community college tuition free.

How do Republicans define Bidenomics?

As little more than a reckless spending binge. Bidenomics means “inflationary Washington spending, costly regulations and regressive taxes,” said Wyoming Senator John Barrasso. Florida Governor and presidential candidate Ron DeSantis, vowing to repeal Bidenomics, pledged to “stop the Congress from borrowing and spending this country into oblivion.”

What do others say?

Felicia Wong of the Roosevelt Institute, a progressive research group, said Biden’s “invest-in-people approach” marks a welcome recognition that governments can and do influence markets through industrial policy. Larry Summers, a Democrat who held top economic posts under Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, said he believes in Biden’s manufacturing and climate change goals, but is “profoundly concerned by the doctrine of manufacturing-centered economic nationalism that is increasingly being put forth as a general principle to guide policy.” Michael Strain, director of economic policy studies at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, argued that other nations likely will retaliate against Biden’s industrial policies, blunting the US’s actions.

What’s been the effect of Bidenomics?

A construction boom, potentially with a side of inflation. Spending on factory construction almost doubled in the past year, spurred on in part by the clean energy and semiconductor subsidies. The building spurt may help the US avoid recession: Moody’s Analytics chief economist Mark Zandi saw Bidenomics making up about 0.4 percentage point of the tepid 1% economic growth rate he was expecting over the next year. “The timing is very propitious,” he said in early August. As for inflation, the potential skunk at the garden party, analysis by Bloomberg Economics in June suggested all the extra spending will boost prices in an already stretched economy, and the Fed may have to raise interest rates by 50 basis points higher than it otherwise would have.

Does every president beget a ‘-nomics’?

To some degree, yes. President Richard Nixon’s structural changes to the international monetary system were shorthanded as Nixonomics, while Carternomics was mostly a pejorative deployed to remember an era of painful inflation. The convention really took off with Reaganomics, which to this day is employed both by fans of Ronald Reagan’s tax-cutting agenda and by critics of the idea that benefits afforded to the well-off “trickle down” to the masses. On a purely linguistic level, the practice seems to work best when attached to a name that ends in N, as “Biden” does, or a vowel, as with Abenomics, a rare example of the practice being applied globally.