Amazon designed its algorithm at Jeff Bezos's urging to be something it wanted to show you, not the cheapest and best product, government claims

When the Federal Trade Commission sued Amazon in September, accusing the e-commerce giant of using illegal tactics to maintain its monopoly, a key thrust of its complaint was that Amazon’s tactics were bad for consumers.

How bad for consumers, exactly? On Thursday, the FTC removed some redactions from its complaint to reveal more details, and it set the scene for a glut of “expensive, irrelevant advertisements” that persist only because they add to Amazon’s profits—and that’s just how founder Jeff Bezos wanted it.

Amazon, which started as a bookseller in 1994, quickly expanded into selling other products and then opened its platform to third-party sellers. Around 2012, the company went into advertising, where it charged sellers and others for product placement on the site.

Starting in 2014, then-CEO Bezos instructed the company “to go big, very big” on ads, according to the government’s complaint. By 2017, ads were all over the top of Amazon’s site, its “most valuable virtual real estate,” per the complaint. Over the course of one year, the number of ads that one mobile search query generated increased fivefold, the FTC claims.

‘Search relevance’ was irrelevant to profits, FTC claims

Did Amazon shoppers like the ads? Bezos didn’t care, the FTC claims, writing that he pushed executives to accept junk ads because they were so profitable: “the revenue generated by advertisements eclipsed the revenue lost by degrading consumers’ shopping experience,” the complaint reads.

“At a key meeting, Mr. Bezos directed his executives to “[a]ccept more defects” as a way to increase the total number of advertisements shown and drive up Amazon’s advertising profits,” the FTC writes, using the term to describe an ad that was irrelevant or only marginally relevant to a shopper’s search term.

“With advertisements being so profitable to Amazon even at higher defect rates, senior Amazon executives agreed, ‘we’d be crazy not to’ increase the number of advertisements shown to Shoppers,” the complaint says. Further on, the FTC quotes “clear guidance” from senior Amazon executives that “advertising should not be constrained by additional guardrails…like…search relevance.”

Not all Amazon workers were on board with this plan, according to the complaint—but they went along with it because the advertising division was critical to the company’s bottom line. One senior executive wryly commented that “it was in the advertising division’s nature as the proverbial ‘scorpion’ to poison organic search results,” according to the complaint.

Amazon disputed this narrative to Fortune. In a prepared statement, company spokesperson Tim Doyle said the FTC’s narrative was “grossly misleading and taken out of context, and does not reflect Amazon’s longstanding dedication to continually improving the customer experience. Amazon works incredibly hard every day to earn customers’ trust, and customer feedback on our shopping experience is consistently positive.”

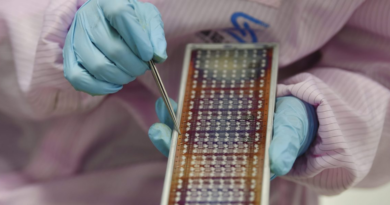

The complaint also reveals more information on a previously identified algorithm Amazon allegedly used to hike prices across the internet. Code-named Project Nessie, the tool was used by Amazon to pinpoint products for which it could raise prices and have other shopping sites follow suit. Amazon activated the algorithm to raise prices on some products, and when other sites followed its lead, it kept the higher prices in place, the FTC said. Project Nessie has generated more than $1 billion in excess profits for Amazon, according to the complaint, which confirmed previous reporting on Project Nessie from the Wall Street Journal.

Doyle told Fortune that Project Nessie was an “old” pricing algorithm that the FTC “grossly mischaracterizes.”

“Nessie was used to try to stop our price matching from resulting in unusual outcomes where prices became so low that they were unsustainable,” Doyle said. “The project ran for a few years on a subset of products, but didn’t work as intended, so we scrapped it several years ago.”