SpaceX acquires parachute company for $2.2M, because it turns out space-rated parachutes are very hard

SpaceX is known for its vertical integration, but one component it’s been outsourcing is parachutes — until earlier this month, when the company quietly acquired parachute vendor Pioneer Aerospace after its parent company went bankrupt. The Information first reported the news.

This is the second known acquisition for SpaceX, which acquired small satellite startup Swarm in 2021 for a $524 million mostly-stock deal. Pioneer is coming much more cheaply: SpaceX has snapped it up for just $2.2 million, according to a bankruptcy filing by Pioneer’s parent company in Florida.

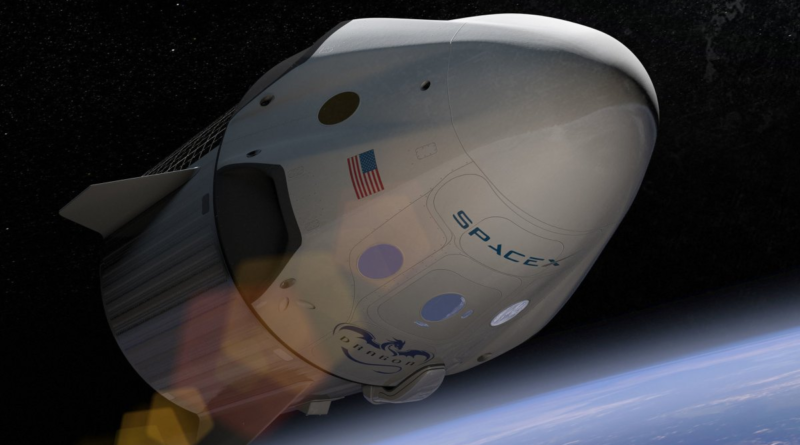

Pioneer provides the drogue parachutes for SpaceX’s Dragon capsules, the spacecraft line that NASA uses to transport cargo and astronauts to and from the International Space Station. Drogue chutes are extremely sophisticated components designed for high velocity; in the case of Dragon, the chute deploys after the capsule has reentered through much of the atmosphere, to stabilize the spacecraft and slow it down a little bit. According to NASA, the two drogues deploy when the Dragon is at 18,000 feet in altitude, moving at around 350 miles per hour. (The main chutes are deployed later during reentry, at around 6,000 feet in altitude; SpaceX buys those from Airborne Systems.)

Saving a vendor from dissolution — which would’ve likely been Pioneer’s fate, given the bankruptcy of its parent company — seems like a strong gesture on the part of SpaceX. But that just points to the real difficulty of making parachutes designed to survive such high speeds.

“Space is hard, but space parachutes are much harder,” Abhi Tripathi, director of mission operations at UC Berkeley’s Space Sciences Laboratory, said in a recent interview. “It’s pretty much among the hardest things, other than a very complex propulsion system, to make.”

He should know: Tripathi’s career includes a 10-year stint at SpaceX, where he was director of Dragon missions and director of flight reliability for the Dragon capsule, and nearly 10 years at NASA, where he worked as a lead aerospace systems engineer.

While SpaceX is famously known for insourcing components, Tripathi said he’s been in meetings with CEO Elon Musk who determines when to outsource based on two factors: that the supplier is not “a complete, incompetent idiot” (Tripathi was paraphrasing Musk here), and that SpaceX can trust that the supplier can deliver on schedule.

“When one or both of those criteria fails, is when SpaceX decides to ask the hard question: Can we insource this? Can we vertically integrate it into our product line?” Tripathi explained.

The knowledge and ability to manufacture such small-volume, technically sophisticated products is hard to replicate quickly — certainly not at the time-scales SpaceX required when it was certifying Dragon. It’s true that SpaceX was heavily involved in the engineering of those drogue shoots — Tripathi pointed me to a recent paper authored by current and former SpaceX engineers on exactly that, and said that SpaceX extensively tested the parachutes itself — the company ultimately looked outward for manufacturing. Hence the deals with Pioneer and Airborne.

“It’s not a science, it’s an art, and it takes lots of testing,” Tripathi said. “Unless you have the capital to do a long testing campaign and really understand the guts of every little part of your parachute system — the linkages, the gores, the reefing lines, the stringers — unless you have a very dedicated test program, you’re not going to understand your own parachutes well enough to know the weak parts of your parachute system.”

Update: The article originally stated that the drogue parachutes are deployed when the Dragon is moving at orbital velocity. It has been corrected to reflect that the drogue chutes deploy after atmospheric reentry.