Private equity firms have avoided taxation on over $1 trillion of income thanks to a loophole, new Oxford research reveals

The largest PE firms in the world have avoided paying income taxes on more than $1 trillion of incentive fees since 2000 alone, according to new research from Oxford University, by making payments in a structure that subjects them to a much lower tax.

Private equity firms now control one-fifth of the U.S market, and can be an important source of foreign capital, but are now the target of politicians calling for crackdowns as governments in need of more revenue are looking for sources to pull from.

The new research, spearheaded by Oxford business professor Ludovic Phalippou, found the largest firms dedicated to private investment strategies—like buyout firms, venture capital, infrastructure, and bankruptcy and debt—have earned more than $1 trillion in carried interest pay since 2000. The main purposes of the research, Phalippou said in an interview with the Financial Times, is to show the colossal wealth created by the high fees of private funds, divulge the potential tax revenue governments could collect from these firms if such fees were treated as income tax rather than capital gains, and to reveal whether private investment strategies are worth what they cost.

“It shows you the upper bound of what you could collect if all of the countries in the world coordinated to tax that pot,” Phalippou said in the interview, adding, “once you understand how much money we are talking about, you can understand why private equity is the largest donor to politicians and universities.”

Senior employees of private equity advisory firms earn salaries that are subject to standard income taxes, the report states, but they also receive payments “conditional on the performance of the funds they advise: the carried interest.”

Most tax laws, he writes in the report, consider carried interest to be a capital gain, and is taxed at a much lower rate than income tax rates. These payments often resemble a performance-related bonus payment, but it comes with an exception that “employees should personally invest in the fund under management to be eligible for this bonus.” It’s a stark difference from how publicly traded firms operate, where as much as half of these fees are paid to shareholders in the form of dividends, the Financial Times reported.

The restructured payments have been dubbed a “loophole” by politicians—and the method has been drawing political scrutiny across the U.S and Europe for years, with the U.K.’s Labour party one of its most vocal critics.

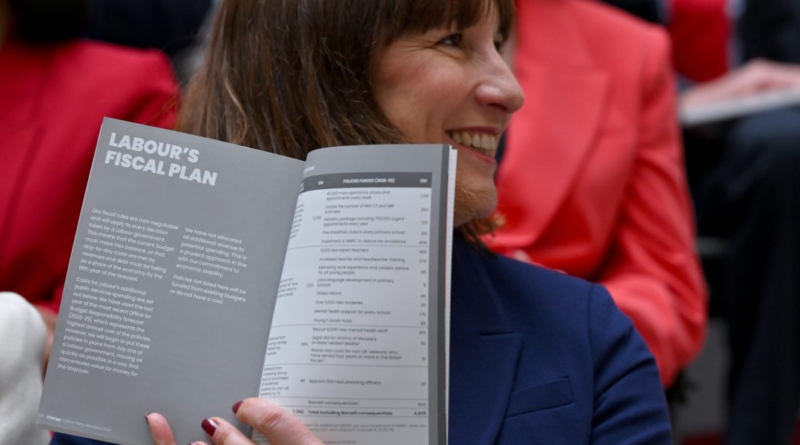

Rachel Reeves—the country’s shadow chancellor and a member of the Labour party, which is widely expected to win this year’s elections—has vowed to move forward with plans to impose higher taxes on top private equity bosses. In its election manifesto published Thursday, the party pledged to consult on closing the carried interest tax loophole, which currently allows private equity bosses to pay tax at 28% capital gains rate, rather than the higher top marginal rate of income tax at 45%.

Reiterating this promise is the party’s latest push in a years-long effort to close the tax loophole, which Reeves has estimated could raise up to £440 million for the U.K government. Critics of the Labour party’s plan cite concerns that higher tax rates will give investment groups more reason to leave London, saying that foreign capital can help address needs that Britain’s stretched public finances cannot fund on their own, like infrastructure, green energy, and more affordable housing.

In the U.S., several politicians including President Joe Biden and even former presidents Barack Obama and Donald Trump all made vows to end the special tax structure, but all those plans cracked under pressure from industry lobbyists.

The savings some top private equity bosses amass are sizable: Phalippou’s research calculates that Blackstone Group, the world’s largest private equity investor, earned $33.6 billion in carried interest—a sum that is over $10 billion larger than any other single investment firm.

Private equity firms have a notorious reputation for overtaking or forming monopolies in several industries by gobbling up publicly traded companies as private firms, which means they are not required by law to disclose information about their finances, operations, business risks, or legal liabilities. Such firms, though, are now in control of one-fifth of the American market, making a large chunk of the economy financially invisible to investors, the media and regulators.

Phalippou’s research is also meant to provide insight on how profitable private investment strategies really are in relation to the financial returns they generate. The report shows the median private equity fund earns just over 1.6-times investors’ money over four to five years, which is comparable to the long-term returns of U.S. stocks.

“It is hard for me to look at these numbers and be amazed,” Phalippou told the FT.

“The $1tn seems quite extraordinary. The return number, not so much,” Phalippou said. “It is good but it is not something to write home about.”