Patagonia became famous for letting staff cut out early to chase waves—now it’s asking dozens of employees to relocate or leave because it’s 300% overstaffed

For more than 50 years, Patagonia has built a reputation as one of the most respected brands on the planet. Aside from producing fleece vests that are equally ubiquitous in corporate offices and mountain lodges, the outdoor-apparel company is known for being outspoken about climate change and for donating a portion of its sales to environmental groups.

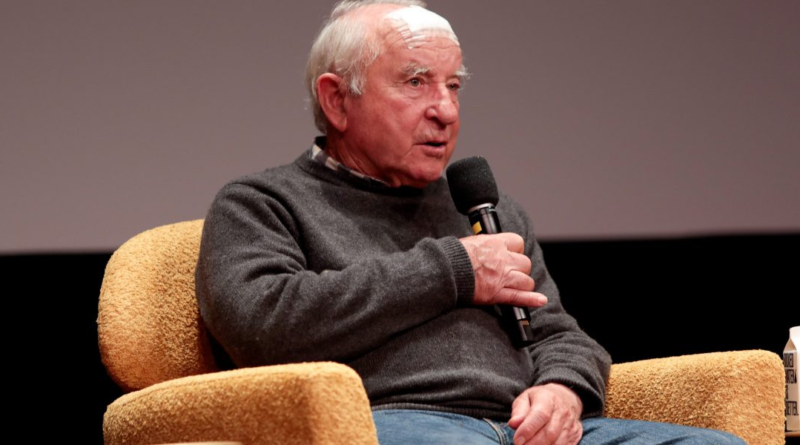

More than that, Patagonia’s conscientious approach to business has long extended to its employees. From the start, Yvon Chouinard, the mystic climber turned entrepreneur who founded the company, set flexible work hours that gave staff the freedom to chase waves when the swells were right, or pick up their kids from school—all part of an alternative approach to business that Chouinard outlined in his autobiography, Let My People Go Surfing.

So it didn’t come as a surprise that when Patagonia announced earlier this week it was asking a third of its customer service staff to either move to one of seven cities in the U.S. or part ways with the company, the decision generated headlines.

Corley Kenna, head of communications at Patagonia, told Fortune that for much of the last year its customer-service team, which has been fully remote since the pandemic, has been anywhere from 200 to 300% overstaffed for much of the last year.

“Many times staff only had about two hours of work a day,” Kenna said. “That’s not good for your career. That’s not good for the business.”

The company began piloting the “hub” model last year, Kenna told Fortune, in large part because of negative feedback it had received about being fully remote.

“Many [employees] missed a lot of the important cultural aspects that come with Patagonia and that come from being near people. They were also concerned about career passing and career growth and feeling a little isolated that way.”

Under the new model, 90 of its 255 staffers are being asked to move within 60 miles of a new “hub” city—Atlanta, Salt Lake City, Reno, Dallas, Austin, Chicago, or Pittsburgh. Workers were asked to make a decision by Friday, and if they chose to move, they had to be relocated by Sept. 30. The company said it would help pay for the cost of relocating.

Some staff say the timeline they were given to make the decision felt rushed and unreasonable.

“It’s a huge decision to make if you’re going to uproot your life and go to another city, and you’re supposed to decide that in two or three days?” one employee told the Ventura County Star, which first reported the decision.

Kenna said she understood why some employees were upset, but that the transition to the hub model was something Patagonia had been transparent about with its employees, and that given the company’s overstaffing problem, it could have happened sooner.

“We wanted to be really intentional, and we wanted to be sure that this was the right model,” she told Fortune. “We knew it would affect a lot of people, and so we took it really seriously to think through all the different ways we could care for our people. So think it’s a fair call-out, but I think that’s our real answer.”

Kenna also said there was some flexibility to the Friday deadline.

In 2023, Patagonia was ranked as the most reputable brand in the world, climbing from third place the year before, according to an annual Harris poll on corporate reputation. It dropped to eighth in 2024.

In 2022, Chouinard and his family gave away their profits from the $3 billion company, splitting the company’s shares into two new trusts designed to address climate change. Since the restructuring went into effect, more than $70 million has been funneled from the business to conservation groups and other nonprofit organizations, according to the New York Times.

“Instead of exploiting natural resources to make shareholder returns, we are turning shareholder capitalism on its head by making the Earth our only shareholder,” chairman Charles Conn wrote in a Fortune op-ed.

But in the wake of this week’s decision, some of the affected employees say the company’s attitude toward employees has shifted.

“I think that the company has changed a lot since it sold to Mother Earth,” an employee told Business Insider. “Since Yvon stepped away, it’s been a slow burn of shifting away from caring about employees.”

Under the restructuring, the Chouinard family still has strong control over the company.

“It’s factually inaccurate to say Yvon has stepped away,” Kenna told Fortune. “He would tell you he’s working harder now than he ever has before.”

“In the past three years, we’ve really worked to ramp up how we communicate and care for our people,” she said. “And I’m sad to hear that people think that we’re doing less of that because we’re working really hard to actually do more.”