Meta turned a blind eye to kids on its platforms for years, unredacted lawsuit alleges

A newly unredacted version of the multi-state lawsuit against Meta alleges a troubling pattern of deception and minimization in how the company handles kids under 13 on its platforms. Internal documents appear to show that the company’s approach to this ostensibly forbidden demographic is far more laissez-faire than it has publicly claimed.

The lawsuit, filed last month, alleges a wide spread of damaging practices at the company relating to the health and well-being of younger people using it. From body image to bullying, privacy invasion to engagement maximization, all the purported evils of social media are laid at Meta’s door — perhaps rightly, but it also gives the appearance of a lack of focus.

In one respect at least, however, the documentation obtained by the attorneys general of 42 states is quite specific, “and it is damning,” as AG Rob Bonta of California put it. That is in paragraphs 642 through 835, which mostly document violations of the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act, or COPPA. This law created very specific restrictions around young folks online, limiting data collection and requiring things like parental consent for various actions, but a lot of tech companies seem to consider it more suggestion than requirement.

You know it is bad news for the company when they request pages and pages of redactions:

Image Credits: TechCrunch / 42 AGs

This recently happened with Amazon as well, and it turned out they were trying to hide the existence of a price-hiking algorithm that skimmed billions from consumers. But it’s much worse when you’re redacting COPPA complaints.

“We’re very bullish and confident in our COPPA allegations. Meta is knowingly taking steps that harm children, and lying about it,” AG Bonta told TechCrunch in an interview. “In the unredacted complaint we see that Meta knows that its social media platforms are used by millions of kids under 13, and they unlawfully collect their personal info. It shows that common practice where Meta says one thing in its public-facing comments to Congress and other regulators, while internally it says something else.”

The lawsuit argues that “Meta does not obtain—or even attempt to obtain—verifiable parental consent before collecting the personal information of children on Instagram and Facebook… But Meta’s own records reveal that it has actual knowledge that Instagram and Facebook target and successfully enroll children as users.”

Essentially, while the problem of identifying kids’ accounts created in violation of platform rules is certainly a difficult one, Meta allegedly opted to turn a blind eye for years rather than enact more stringent rules that would necessarily impact user numbers.

Meta, for its part, said in statements that the suit “mischaracterizes our work using selective quotes and cherry-picked documents,” and that “we have measures in place to remove these [i.e. under-13] accounts when we identify them. However, verifying the age of people online is a complex industry challenge.”

Here are a few of the most striking parts of the suit. While some of these allegations relate to practices from years ago, bear in mind that Meta (then Facebook) has been publicly saying it doesn’t allow kids on the platform, and diligently worked to detect and expel them, for a decade.

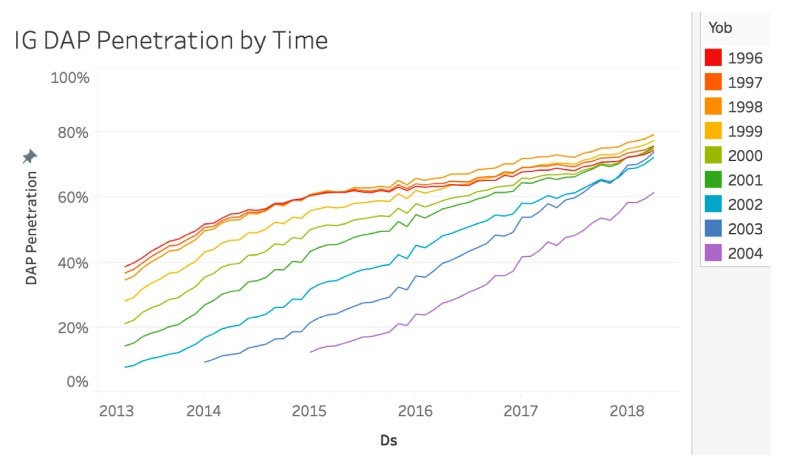

Meta has internally tracked and documented under-13s, or U13s, in its audience breakdowns for years, as charts in the filing show. In 2018, for instance, it noted that 20% of 12-year-olds on Instagram used it daily. And this was not in a presentation about how to remove them — it is relating to market penetration. The other chart shows Meta’s “knowledge that 20-60% of 11- to 13-year-old users in particular birth cohorts had actively used Instagram on at least a monthly basis.”

The newly unredacted chart shows that Meta tracked under-13 users closely. Image Credits: Meta

It’s hard to square this with the public position that users this age are not welcome. And it isn’t because leadership wasn’t aware.

That same year, 2018, CEO Mark Zuckerberg received a report that there were approximately 4 million people under 13 on Instagram in 2015, which amounted to about a third of all 10-12-year-olds in the U.S., they estimated. Those numbers are obviously dated, but even so they are surprising. Meta has never, to our knowledge, admitted to having such enormous numbers and proportions of under-13 users on its platforms.

Not externally, at least. Internally, the numbers appear to be well documented. For instance, as the lawsuit alleges:

Meta possesses data from 2020 indicating that, out of 3,989 children surveyed, 31% of child respondents aged 6-9 and 44% of child respondents aged 10 to 12-years-old had used Facebook.

It’s difficult to extrapolate from the 2015 and 2020 numbers to today’s (which, as we have seen from the evidence presented here, will almost certainly not be the whole story), but Bonta noted that the large figures are presented for impact, not as legal justification.

“The basic premise remains that their social media platforms are used by millions of children under 13. Whether it’s 30 percent, or 20 or 10 percent… any child, it’s illegal,” he said. “If they were doing it at any time, it violated the law at that time. And we are not confident that they have changed their ways.”

An internal presentation called “2017 Teens Strategic Focus” appears to specifically target kids under 13, noting that children use tablets as early as 3 or 4, and “Social identity is an Unmet need Ages 5-11.” One stated goal, according to the lawsuit, was specifically to “grow [Monthly Active People], [Daily Active People] and time spent among U13 kids.”

It’s important to note here that while Meta does not permit accounts to be run by people under 13, there are plenty of ways it can lawfully and safely engage with that demographic. Some kids just want to watch videos from SpongeBob Official, and that’s fine. However, Meta must verify parental consent and the ways it can collect and use their data is limited.

But the redactions suggest these under-13 users are not of the lawfully and safely engaged type. Reports of underage accounts are reported to be automatically ignored, and Meta “continues collecting the child’s personal information if there are no photos associated with the account.” Of 402,000 reports of accounts owned by users under 13 in 2021, fewer than 164,000 were disabled. And these actions reportedly don’t cross between platforms, meaning an Instagram account being disabled doesn’t flag associated or linked Facebook or other accounts.

Zuckerberg testified to Congress in March of 2021 that “if we detect someone might be under the age of 13, even if they lied, we kick them off.” (And “they lie about it a TON,” one research director said in another quote.) But documents from the next month cited by the lawsuit indicate that “Age verification (for under 13) has a big backlog and demand is outpacing supply” due to a “lack of [staffing] capacity.” How big a backlog? At times, the lawsuit alleges, on the order of millions of accounts.

A potential smoking gun is found in a series of anecdotes from Meta researchers delicately avoiding the possibility of inadvertently confirming an under-13 cohort in their work.

One wrote in 2018: “We just want to make sure to be sensitive about a couple of Instagram-specific items. For example, will the survey go to under 13 year olds? Since everyone needs to be at least 13 years old before they create an account, we want to be careful about sharing findings that come back and point to under 13 year olds being bullied on the platform.”

In 2021, another, studying “child-adult sexual-related content/behavior/interactions” (!) said she was “not includ[ing] younger kids (10-12 yos) in this research” even though there “are definitely kids this age on IG,” because she was “concerned about risks of disclosure since they aren’t supposed to be on IG at all.”

Also in 2021, Meta instructed a third-party research company conducting a survey of preteens to remove any information indicating a survey subject was on Instagram, so the “company won’t be made aware of under 13.”

Later that year, external researchers provided Meta with information that “of children ages 9-12, 45% used Facebook and 40% used Instagram daily.”

During an internal 2021 study on youth in social media described in the suit, they first asked parents if their kids are on Meta platforms and removed them from the study if so. But one researcher asked, “What happens to kids who slip through the screener and then say they are on IG during the interviews?” Instagram Head of Public Policy Karina Newton responded, “we’re not collecting user names right?” In other words, what happens is nothing.

As the lawsuit puts it:

Even when Meta learns of specific children on Instagram through interviews with the children, Meta takes the position that it still lacks actual knowledge of that it is collecting personal information from an under-13 user because it does not collect user names while conducting these interviews. In this way, Meta goes through great lengths to avoid meaningfully complying with COPPA, looking for loopholes to excuse its knowledge of users under the age of 13 and maintain their presence on the Platform.

The other complaints in the lengthy lawsuit have softer edges, such as the argument that use of the platforms contributes to poor body image and that Meta has failed to take appropriate measures. That’s arguably not as actionable. But the COPPA stuff is far more cut and dry.

“We have evidence that parents are sending notes to them about their kids being on their platform, and they’re not getting any action. I mean, what more should you need? It shouldn’t even have to get to that point,” Bonta said.

“These social media platforms can do anything they want,” he continued. “They can be operated by a different algorithm, they can have plastic surgery filters or not have them, they can give you alerts in the middle of the night or during school, or not. They choose to do things that maximize the frequency of use of that platform by children, and the duration of that use. They could end all this today if they wanted, they could easily keep those under 13 from accessing their platform. But they’re not.”

You can read the mostly unredacted complaint here.

(This story has been updated with a comment from Meta.)