A British sci-fi writer correctly predicted almost everything about modern living 60 years ago, from AI to remote work

“The only thing we can be sure of about the future is that it will be absolutely fantastic, so, if what I say now seems to you to be very reasonable, then I’ll fail completely.”

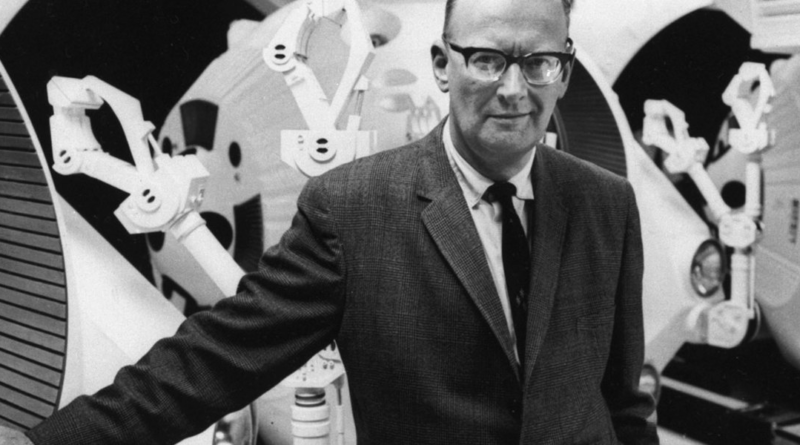

That’s the auspicious opening line in a segment from BBC’s Horizon program, in an episode titled “The Knowledge Explosion,” originally broadcast in September 1964 and delivered straight to camera by Arthur C. Clarke, one of Britain’s most well-regarded science fiction writers and the author of 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Clarke, known for his love of space travel and undersea exploration, posited that the city of the future—he used the year 2000 as his touchstone, an incomprehensibly long time away—would hardly exist at all. Not because of a nuclear holocaust or wasteland pandemic. Rather, it would be due to incredible breakthroughs in telecommunications.

“These things will make possible a world in which we can be in instant contact with each other wherever we may be, where we can contact our friends anywhere on earth even if we don’t know their actual physical location,” Clarke said. (Check, check, check–though location knowledge is no longer an obstacle, thanks to apps like Find My.)

Stanford economist and work-from-home expert Nick Bloom shared the unearthed broadcast on LinkedIn earlier this week, commending Clarke for his stunningly accurate predictions. Namely, Clarke was spot-on in predicting distributed work.

“It will be possible—perhaps only 50 years from now—for a man to conduct his business from Tahiti or Bali just as well as he could from London,” Clarke said. “In fact, if it proves worthwhile, almost any executive skill, any administrative skill, even any physical skill, could be made independent of distance. I am perfectly serious when I suggest that one day we may have brain surgeons in Edinburgh operating on patients in New Zealand.”

Clarke’s work predictions, in particular, have been exceptionally accurate. “The traditional role of the city as a meeting place for men would have ceased to make any sense. In fact, men will no longer commute. They will communicate.” (To be sure, cities haven’t quite gone obsolete, but a mass-move towards remote work has led to the hollowing out of office buildings, the decimation of retail in business districts, and an explosive donut effect in outer suburbs.)

Clarke even touched on machine learning, what we’d now ubiquitously call AI: “The most intelligent inhabitants of that future world won’t be men or monkeys,” he posited. “They’ll be machines.” Echoing the wary comments of the so-called godfather of AI, Geoffrey Hinton, Clarke said he expects machines to outsmart humans. “They will start to think, and eventually they will completely outthink their makers. Is this depressing? I don’t see why it should be. We superseded the Cro-Magnons and Neanderthal men and we presume we’re an improvement.”

Further, Clarke was an early AI optimist, urging people to regard newfangled tech as “a privilege” and a “stepping stone to higher things.” Human evolution has “about come to its end,” Clarke said. “And we’re now at the beginning of inorganic or mechanical evolution, which will be thousands of times swifter.” Worry not, though: “Human beings are almost infinitely adaptable.”

Clarke concluded by reminding viewers not to be pessimistic or nervous; the future is “endlessly fascinating” insofar as despite humans’ best efforts, “we will never outguess it.”

Never is a strong word; Clarke came pretty close.